The word monument is derived from the Latin verb monere, meaning “to remind,” “to advise,” and “to warn.” It is from monere that we also get words like demonstrate, to show something; remonstrate, to make a forcefully reproachful protest; and monster. Monsters have functioned allegorically throughout history, often sent from above as a warning to humankind.

An inflatable sculpture, Behemoth, invokes the redacted monuments shrouded in black tarps in cities like Charlottesville and Chicago. Perpetually rising and falling, it suggests the ongoing cruelty of deferral and debate around the removal of these monuments, and the desire to preserve them instead of the communities that continue to fight for liberation.

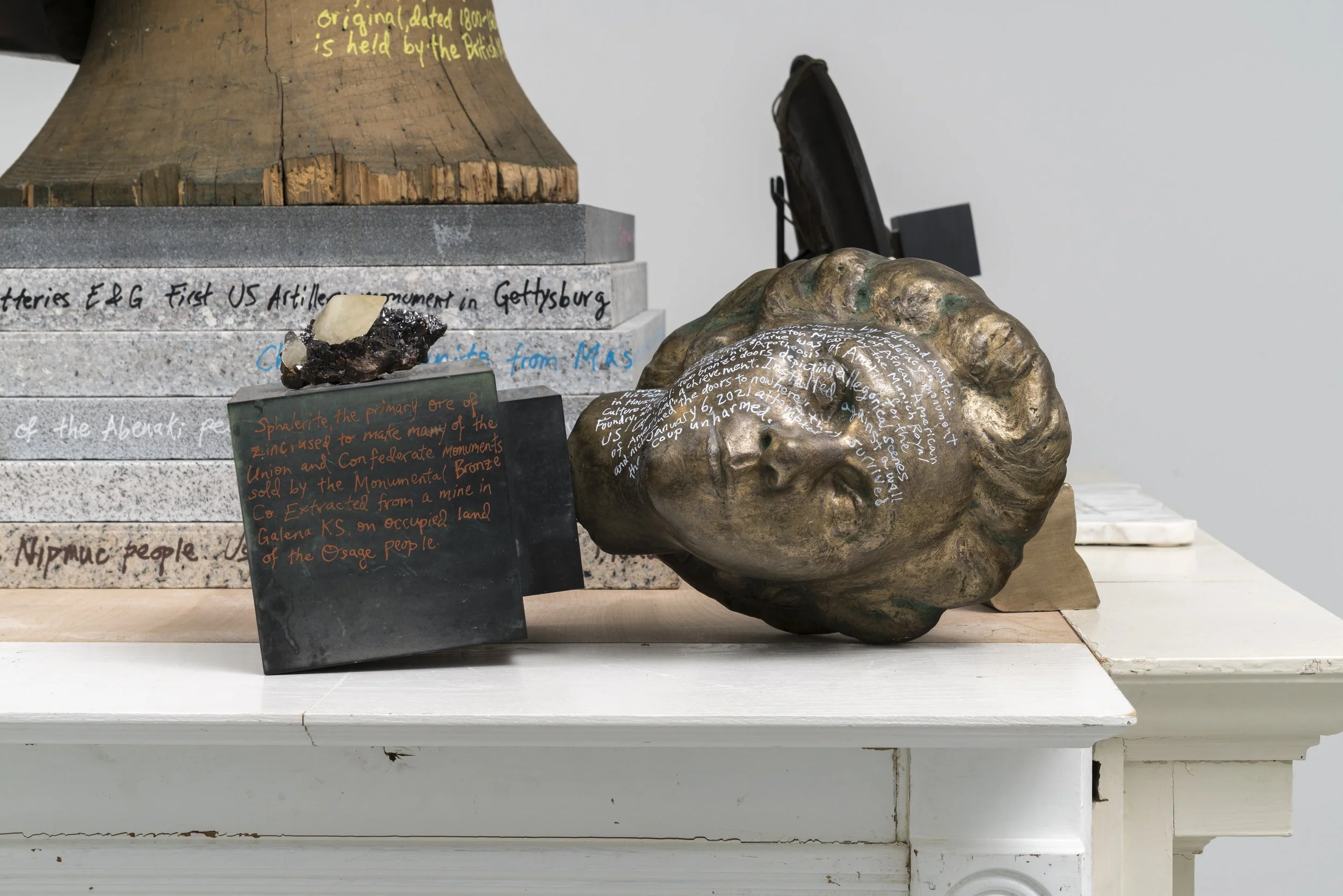

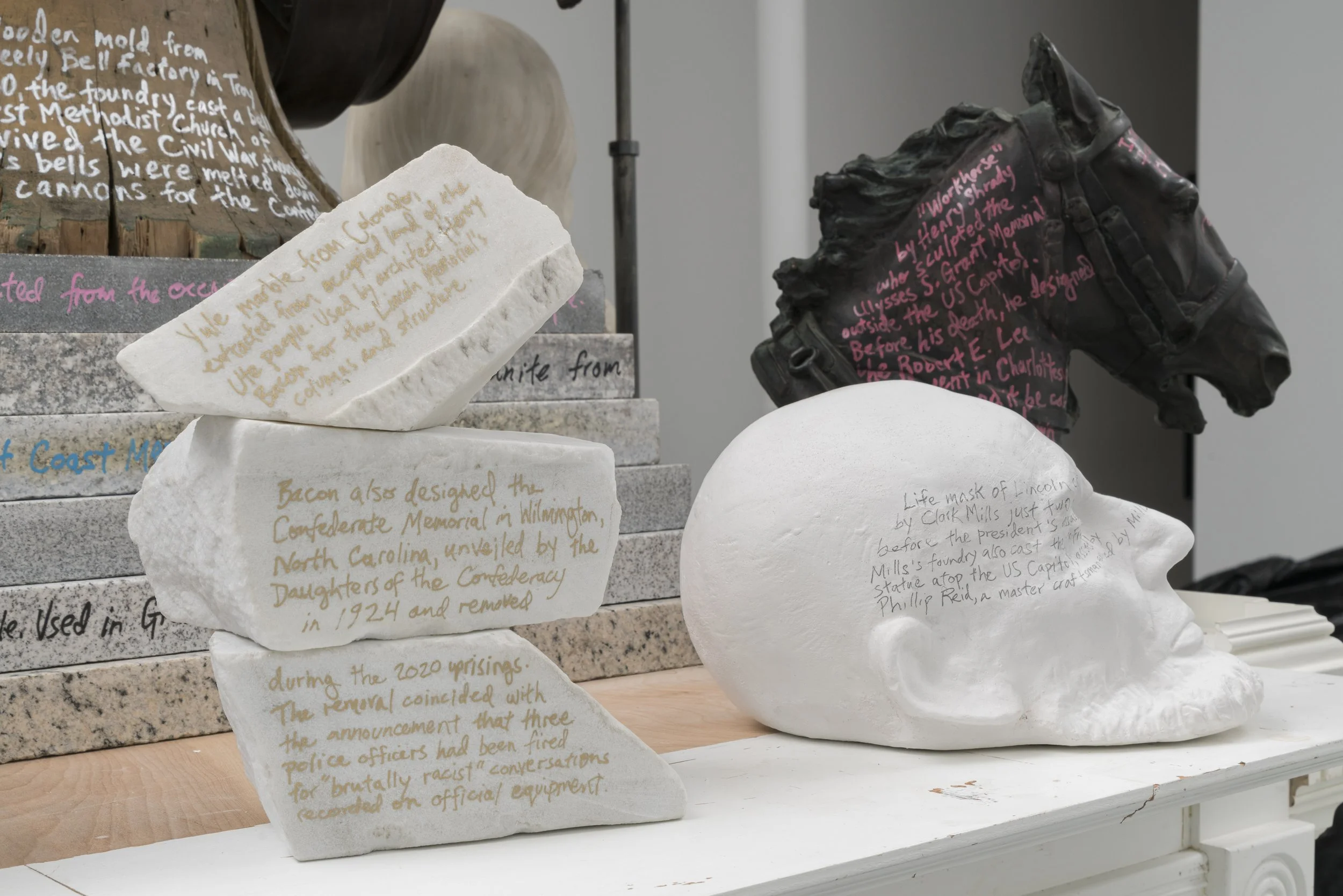

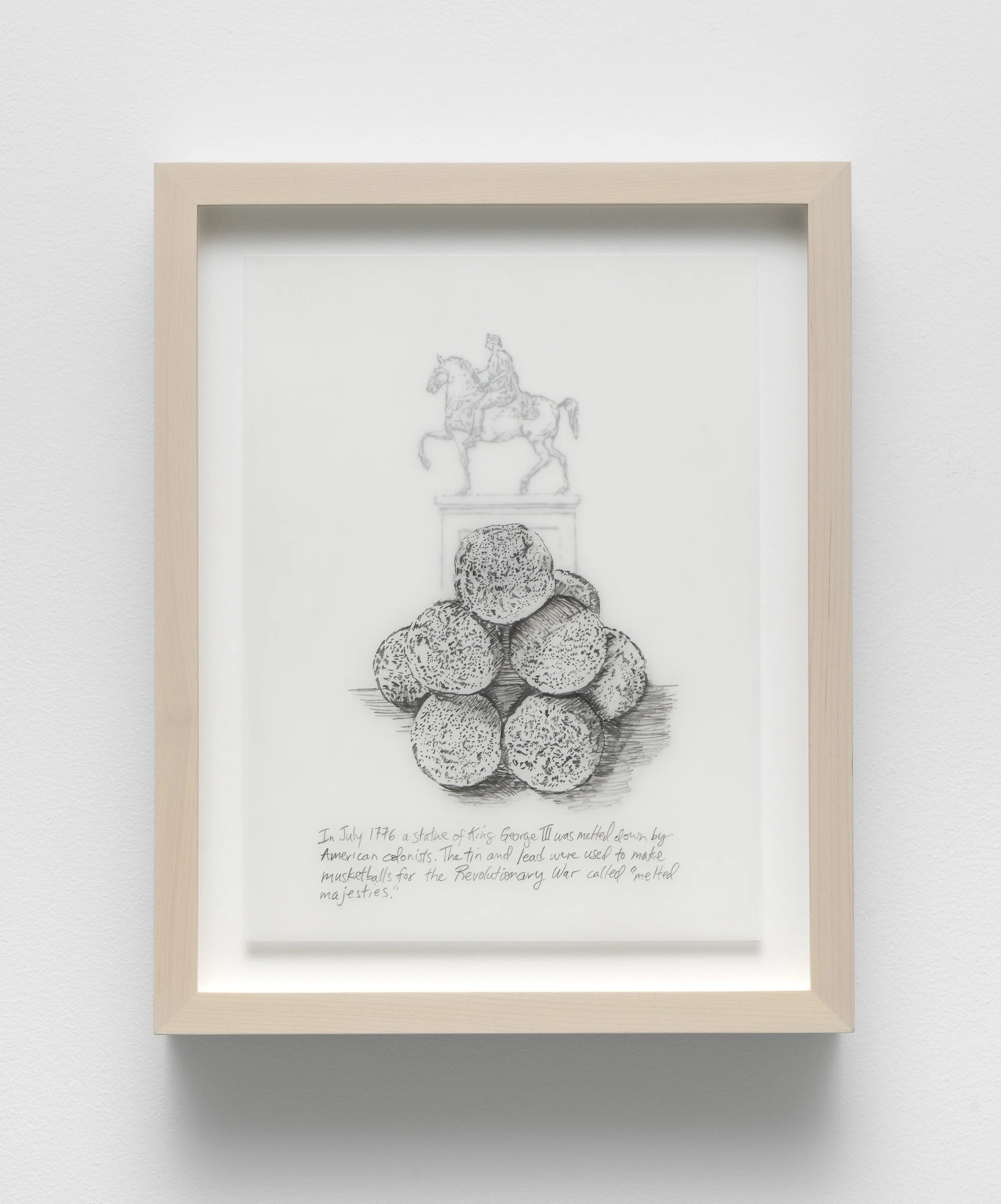

America’s public spaces are occupied by markers that function less as memorials than as warnings, sculpting centuries of settler colonialism, white supremacy and imperialism. Looking closely at the history of these monuments, it becomes clear that artists like Henry M. Shrady, who designed the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial in Washington, DC, and the recently removed Robert E. Lee Monument in Charlottesville, Virginia, created work valorizing both sides of the American Civil War